By Melkorka Licea

An herbal supplement called kratom — hailed by some as a miracle cure for heroin addiction, and assailed by others as a deadly habit-forming substance in itself — is flying off the shelves at dozens of New York city smoke shops and cafes.

The Southeast Asian plant-based drug is currently in regulatory limbo, legal in New York and 42 other states, but on a federal watch list while the Food and Drug Administration decides whether to characterize it as a dangerous drug or a benign over-the-counter herbal remedy. For now, the feds have labeled kratom a “drug of abuse” and a “drug of concern.”

“They could decide tomorrow or three months from now — we have no idea what their timeline is,” said Melvin Patterson, spokesman for the federal Drug Enforcement Administration. “Until then our hands are tied.”

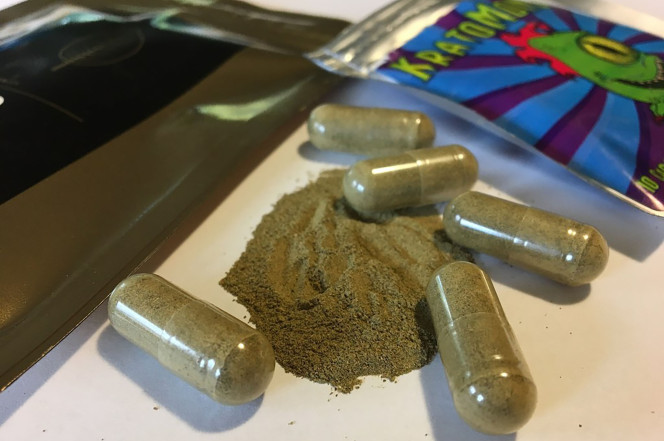

While the feds marinate on what to do about kratom, hipsters and health nuts from Bushwick to the East Village are scooping up the ground leaves — in powder or capsule form — for as little as $5 per two-gram dose. Depending on the strain, they use it to douse an addiction, dampen pain or party on a Friday night.

“It’s become my best-selling product,” said Ali Muhammad, who manages four East Village smoke shops that carry kratom.

“I have a lot of first-time buyers, but also a lot of regular patients who buy it in bulk.”

The varieties are grouped and labeled by brand, potency and strain. Red kratom is said to have pain-killing properties. White is supposed to boost energy. The most popular is a $30 package of 30 “maeng da” [oddly, Thai slang for water bug or pimp] made by a brand called OPMS. It reportedly makes users alert and focused.

“It’s the best bang for your buck,” Muhammad said.

Muhammad said some regulars use kratom for pain. And some are becoming addicted.

“People will come in every week and stock up on it,” he said. “You can tell they don’t just want it — they need it.”

Since the beginning of the year, the demand for kratom has “blown up,” Muhammad said, and he’s now selling at least 10 packages daily at every location.

The booming popularity ignores kratom’s harmful potential, says the DEA, which counts 15 deaths in the US linked between 2014 and 2016 linked to the substance. Kratom intoxication, often in concert with other drugs, has reportedly led to suicide, psychosis, bleeding in the lungs, seizures and heart palpitations. There have been no known kratom-linked deaths in New York City.

Addiction is also taking many kratom users by surprise.

“People seemed to accidentally get addicted after trying it as a supplement or to help get off harder drugs,” said the DEA’s Patterson. “Then they struggle to get off it.”

Ryan Lloyd, 26, credits kratom with helping him kick a four-year heroin habit seven months ago. In fact, the Bushwick, Brooklyn, resident now serves the elixir to others at the House of Kava.

“It took away my withdrawal symptoms and made me feel like a normal person,” he said. “When going cold turkey, a serious depression sets in and it’s hard to see the end of the tunnel.”

But it’s not a panacea, Lloyd warns.

“I feel like I just became dependent on something else,” he said, admitting he continues to use it. “I don’t want to have a crutch — I want to be sober.”

On East 10th Street near First Avenue, Kavasutra serves the bitter tea hot, even though it’s not listed on the menu. The chain, with locations in Florida and Colorado, mostly offers kava, another plant-based drink, but carries kratom tea in bottles and the powder in plastic baggies. The dimly lit black-lacquer bar has 15 stools and attracts an assortment of locals in the middle of the day.

James Peterson is a regular and says he drank kratom tea twice a day for six months after dislocating his shoulder when he fell three stories on a construction job.

“My doctor wanted to give me painkillers, but I didn’t want to get addicted to them,” said Peterson, 50. “My friend suggested kratom and . . . [once] I started drinking it, I could move my shoulder again. It was totally healed.”

Located on Stanhope Street and Central Avenue in Bushwick, House of Kava feels like someone’s living room, with couches, free Cheetos and mismatched decor. They serve kava and three different kratom teas with varying potency, for $5, $8 and $10.

“As a kavatender I don’t feel guilty serving drinks — like a bartender might,” said an employee mixing up kratom tea blends in beer mugs.

He even serves minors, since there is no legal prohibition against it. A bill that would ban the sale of kratom to anyone under the age of 21 has been gathering dust in committee for two years in the state Assembly.

Owner Joyci Borovky, 24, opened the bar in February 2016, and believes kratom is a much healthier option for recovering addicts than prescribed drugs like suboxone or methodone.

“Those things are highly addictive and intoxicate your mind,” said Borovsky. “You can go about your day completely normally after taking kratom.”

Five blocks away, Brooklyn Kava looks more like a coffee shop than a dive bar — but stays open until midnight.

“The weekend is the best time for selling kratom,” said owner Harding Stowe, 31. “People think of it as an alternative to going to the bar and drinking alcohol. Plus you don’t get a hangover.”

The cafe offers kratom cocktails that are mixed with ginger ale, hibiscus and chai tea for $12.

Critics say the burgeoning kratom culture is misleading.

“These sellers advertise it as a totally benign thing when, in fact, there’s a dangerous side,” said a woman whose girlfriend is addicted to kratom and went through severe withdrawal, just like a heroin addict would.

“She was vomiting, shaking and sweating,” said the woman, who requested anonymity. “When she hadn’t had it in half a day, she couldn’t walk down the sidewalk. She had to constantly be next to a bathroom.”

Kratom comes from a plant known scientifically as Mitragyna speciosa, which is in the coffee family. Its active chemicals bind to the same brain receptors as opioids do.

In a series of studies led by University of Mississippi microbiologist Christopher McCurdy, the active chemical in kratom called mitragynine was found to stop withdrawal symptoms from opioids in mice.

The studies also indicated that the other active chemical in the plant, called 7-hydroxymitragynine, may have low-grade addictive qualities.

While kratom has long been used in Asia to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms, according to a DEA factsheet, in 2016 the DEA tried to designate it as a Schedule 1 controlled substance at the same level as heroin and LSD. But that action was postponed while public comment was solicited.

The agency received over 20,000 statements from the public, 90 percent of which were supportive of keeping kratom legal.

“Most people were self-treating for some sort of chronic pain and former addicts of some sort of opioid,” said Patterson, who estimated 25 percent of respondents were former opioid abusers and 65 percent pain sufferers.

But about 10 percent were kratom addicts. “Some people said they had to go to rehab because of this,” said Patterson. “They said they lost all their money from buying kratom.”

“So where does the truth lie?” Patterson asked. “I’d say probably somewhere in between.”