The Stop the Importation and Trafficking of Synthetic Analogues Act (SITSA) would give the Attorney General unilateral power to ban drugs for up to five years

Jun 27 2018, 5:34pm

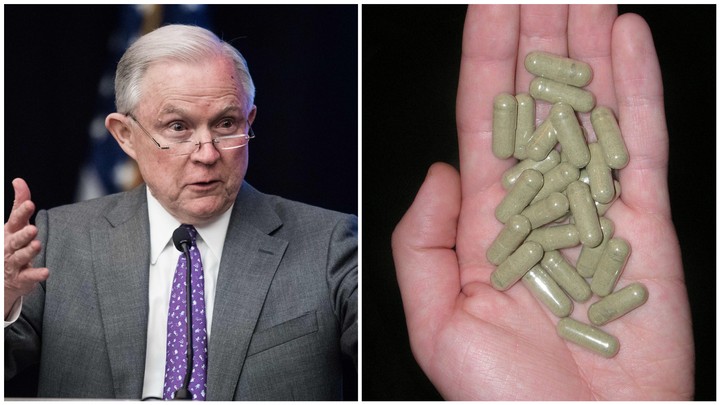

Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images; Wikimedia Commons

On Friday, an overwhelming bipartisan majority in the House of Representatives passed HR 6, or the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) Act.

The bill, which largely addresses the opioid overdose crisis, is stuffed with different measures—nearly 60 individual laws, all previously passed by the House. HR 6 contains reforms for Medicare and Medicaid, requires the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to streamline development of non-addictive painkillers, and will increase access to life-saving drugs like buprenorphine and naloxone.

However, included in this tangle of legislation is a bill called the SITSA Act, or HR 2851. The Stop the Importation and Trafficking of Synthetic Analogues Act is aimed at prohibiting analogs of drugs such as fentanyl from entering the US. Fentanyl is an opioid whose many cousins, like carfentanil, dominate overdose deaths. It should be noted, however, that all fentanyl analogs are already banned, even those that don’t currently exist yet.

But SITSA would also give unilateral drug “scheduling” powers to the Attorney General’s office, allowing the Department of Justice to outlaw substances and set penalties without oversight.

“The typical process, where there is scientific and public health input when deciding whether a drug should be scheduled or not, will be completely eroded,” says Michael Collins, deputy director at the Drug Policy Alliance. “Non-scientific people like the DEA will be making the decisions.”

Under the Controlled Substances Act, a hierarchical system put in place by the Nixon Administration in 1970, there are five brackets for drugs based on their potential for abuse. Schedule I, which covers the most “dangerous” drugs with no accepted medical benefits, includes LSD and marijuana. SITSA would create a sixth group, “Schedule A,” which stamps a temporary ban up to five years—which isn’t “subject to judicial review”—on any molecule that’s chemically similar to a drug that’s already banned and that the DOJ fears is even slightly psychoactive.

Any compound that merely resembles a banned drug and has “an actual or predicted stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogenic effect on the central nervous system” similar to a banned drug can be placed into the new Schedule A at AG Jeff Sessions’s discretion, which has many worried that SITSA could lead to a ban on substances like kava and, of course, kratom.

The federal government has been looking to blacklist kratom, a medicinal plant from Southeast Asia, for several years now, with efforts at the FDA escalating earlier this year. Kratom is used by an estimated 3 to 5 million people in the United States for chronic pain, anxiety, and sometimes to wean off opioids.

Watch More From Tonic:

After using a computer model that showed several of the active chemicals in kratom leaves activate opioid receptors in the brain, the FDA in February declared kratom an opioid with potential for abuse, meaning it could be banned under SITSA. But not all opioids are created equal—some are vastly less dangerous than others—and there are no reports that kratom can make you stop breathing if you overdose.

Kratom has been used in Thailand and throughout Southeast Asia for centuries without reports of death. The FDA has pointed to 44 deaths linked to kratom, but it’s not clear that kratom was solely responsible in any of these cases. If SITSA passes as part of HR 6, it would be easy for the Attorney General to put kratom—or whatever substance they wanted—in Schedule A, which would threaten users with up to 10 years in prison.

SITSA is deeply unpopular with Human Rights Watch, which condemned it in a June 13 letter to Congress as “a gross overreach for one agency within one branch of government, and likely violates the separation of powers.” The letter further noted that the bill “would disproportionately incarcerate low-level drug offenders who did not import or package the drugs, and often are unaware of the chemical composition of the drugs. Many more people would be incarcerated for selling drugs to support their own substance use disorder.” It was signed by 14 other groups including the Drug Policy Alliance, the Harm Reduction Coalition, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the NAACP.

While mere possession of Schedule A substances won’t carry civil or criminal penalties per the bill, the HRW warns that the act isn’t specific enough. “Although SITSA includes a carve out for possession, it will not prevent mass incarceration of low-level drug offenders, in part because quantities that constitute possession are not defined,” they wrote.

Collins, of the Drug Policy Alliance, added that the movement for sentencing reform is built upon the idea that federal drug laws, including the way we schedule drugs, is flawed and has lead to racially biased outcomes and mass incarceration. “That same movement will not support legislation that adds more drugs to that flawed scheduling system,” he says. “And It will definitely not support legislation that grants broad power to any Attorney General—but especially this drug-war loving Attorney General—to unilaterally decide which drugs are made illegal and set the penalties accordingly. That is a very dangerous path that we must avoid.”

“From a public health standpoint, there is no reason to believe this law will have any beneficial effects,” says Marc Swogger, an associate psychiatry professor at University of Rochester Medical Center who studies substance use. “In general, prohibition does not work and often creates illicit markets, which in the US could worsen our problem with mass incarceration.”

Along with eight other scientists, Swogger delivered a letter to Congress on June 21 that said, “[T]here are no safety data to support the conclusion that kratom poses an imminent public health risk to consumers that would justify its scheduling.”

Rep. John Katko of New York, who introduced SITSA, did not respond to Tonic’s requests for comment.

“Banning kratom now is insane from a public health standpoint,” Swogger says, “with the potential to negatively impact pain management, the overdose crisis, and mass incarceration. It is also an attack on a basic civil liberty.”

Swogger, who has published several reviews on kratom abuse, is concerned that a ban will lead to more opioid overdose deaths, not less. “For people with chronic pain, I think a ban will result in decreased quality of life and, potentially, suicides,” he says.

Mac Haddow, the top lobbyist at the American Kratom Association, which was associated with the June 21 letter sent to Congress, says the organization he represents is less concerned with SITSA on its face, and more with how it will be interpreted.

“The problem we have is the definition of what an analog of an opioid or substance might be,” Haddow says. “We are in the process of seeking an amendment [to SITSA] that simply exempts any natural botanical substance, including its constituents and alkaloids, that would be subject to normal scheduling rules. Then it’s based on the medical science, and so with that amendment, we would fully support the SITSA bill.”

Known as the Pocan-Gosar-Polis Amendment, after the representatives who introduced it to the House Rules Committee, it was defeated in a 6 to 4 vote. The AKA will try to insert it again in the Senate’s version of SITSA; which has been introduced and referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. The Senate version is sponsored by Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa. (Grassley’s office did not respond to Tonic’s emailed request for comment by press time; we’ll update this post if we hear back.) The AKA has issued a “call to action” about HR 6, urging its followers to contact their Senators. The bill has been read in the Senate, but a vote is not scheduled at this time.

Given the FDA and the DEA’s track record on kratom—not to mention Sessions’s blatant distaste for almost anything psychoactive—kratom and other substances will likely be in the crosshairs of the feds the moment SITSA becomes law. If advocates want to continue having access to their herb of choice, the fight is just beginning.