As opioid overdose deaths continue to surge, one drug has come out ahead of all the other killers in Virginia – and many may not have known they were even using it.

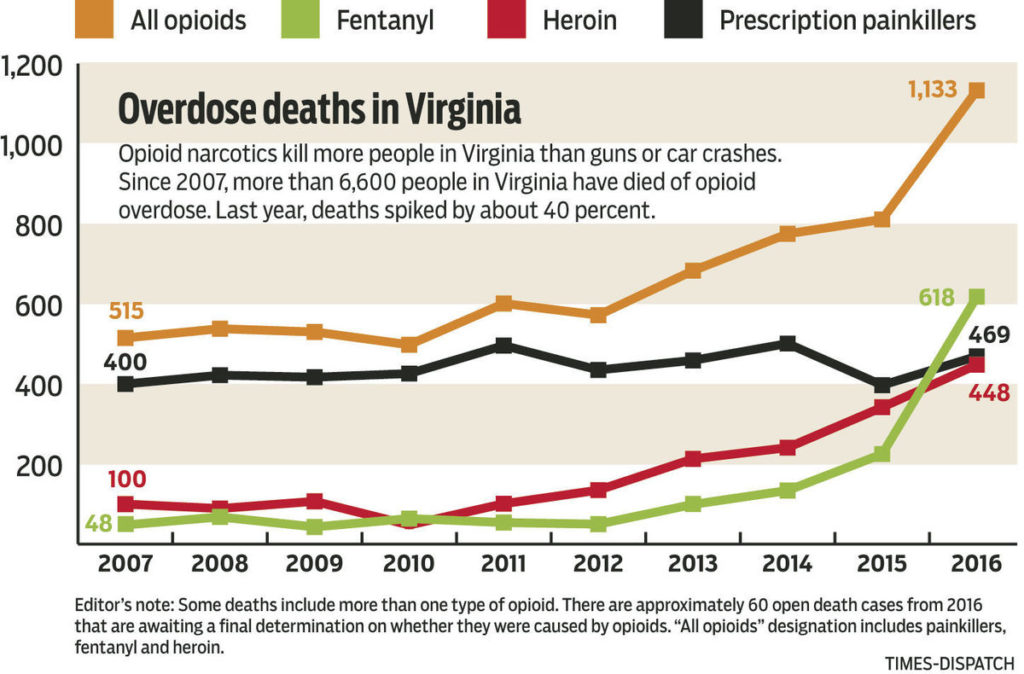

Fentanyl became the deadliest drug in the state last year, surging past heroin and prescription painkillers. Evidence that the painkiller epidemic gave rise to a new wave of heroin use has continued to grow, with illegal opioid deaths outnumbering prescription opioid deaths since 2013.

Of the 1,133 people who died due to opioid overdoses last year, fentanyl contributed to 618 deaths, heroin contributed to 448 deaths, and prescription opioids contributed to 469 deaths.

“It’s all economics,” said Capt. Michael Zohab with the Richmond Police Department. “It’s so cheap to get fentanyl… and if an individual adds fentanyl to what they’re selling as heroin, they can make a lot more money.”

Meanwhile, Zohab said many of the people killed by fentanyl probably do not know they’re using it, as they assume they’re just purchasing heroin on the street.

“What we’re seeing is that a lot of what the (people who use heroin) are using is being mixed with fentanyl and being substituted, and so they’re overdosing because they don’t know what they’re buying,” said Rosie Hobron, a forensic epidemiologist with the state Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

Fentanyl can be more efficient to produce than heroin because it is typically just developed in a warehouse, whereas heroin requires many hundreds of acres to grow the necessary poppies.

“We’re seeing that the precursor chemicals are coming from China, sometimes (sent) directly into the southwest U.S. and other times into Mexico, then made into fentanyl and shipped to Virginia,” said Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring. “This is a frightening development.”

***

Fentanyl was not always a shadowy street drug that was found laced in heroin. Before 2013, most deaths were caused by fentanyl that was produced pharmaceutically as a painkiller. By 2016, most deaths were caused by illicitly produced fentanyl.

Steven LaPrade, who grew up in south Chesterfield and now is a resident with the nonprofit McShin Foundation, began using opioids when he was 15 and eventually began using his dad’s fentanyl prescription about three years ago. LaPrade, 26, has been clean for about six months and stays away from all drugs, even over-the-counter medication like ibuprofen.

“I’ve done just about every opioid you can imagine,” he said. “But fentanyl is so much stronger. There’s nothing compared to it. It’s truly the worst stuff I’ve ever experienced. There’s no happy medium with it. You either don’t do enough or you do too much.”

LaPrade typically used prescription opioids, sometimes using street drugs like heroin, even occasionally mixing heroin and fentanyl, which is how many people experience fatal overdoses.

“I am one of the extremely lucky ones,” he said. “I truly don’t know to this day how I’m still alive.”

***

Meanwhile, as overdose deaths continue to rise, so too do the sometimes unforeseen consequences of drug use.

In conjunction with the opioid epidemic, state health officials have noticed a boom in the number of hepatitis C cases in Virginia over recent years due to injection drug users sharing needles.

While the Department of Health is now finalizing its 2016 hepatitis C numbers, it has finalized its month-over-month report for last year, which are preliminary. Between January and December, there were more than 10,600 chronic cases of hepatitis C, compared with 8,193 in 2015 and about 6,675 in 2014.

With 830 cases, Richmond had more chronic hepatitis C cases than anywhere else in the state last year.

Laurie Forlano, Virginia’s state epidemiologist, noted that health officials watch the number of people infected with hepatitis C by age particularly closely. If younger people, ages 18 to 30, develop hepatitis C, it is more likely a result of injection drug use.

“That curve is steeply increasing around the state,” she said. “That’s a really concerning trend.”

Hepatitis C travels quickly through needle use, and slower to spread is HIV, another bloodborne pathogen. In 2015, Scott County, Ind., saw an outbreak of HIV that was preceded by sharp rises in its cases of hepatitis C.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report last year identifying the hundreds of counties in the country where an HIV outbreak is likely to occur, based on what happened in Scott County.

Eight of the counties are in Virginia: Buchanan, Dickenson, Russell, Lee, Wise, Tazewell, Patrick and Wythe.

To combat the rising rate of hepatitis C and to prevent an HIV outbreak, the Department of Health encouraged the General Assembly to legalize syringe services programs – otherwise known as needle exchange programs – during the most recent session.

Forlano said the Department of Health is preparing to launch the programs once the new law becomes effective July 1. They will be implemented in particular counties where the need is highest, rather than as statewide program.

During an interview last week, Forlano said it was too early to identify in which counties the programs would be launched.

***

While use of fentanyl may have been increasing since 2013, last year the state saw a sharp spike in overdoses caused by cocaine.

From 2013 to 2015, there were only incremental increases in the number of cocaine overdose fatalities. But in 2016, 292 people died from cocaine overdoses, up from 174 the year before.

“It’s not contributing to that many deaths right now, but it is on the rise, and that’s just something that’s concerning because we don’t know… if it’s being mixed with other drugs or if people are taking it alone,” Hobron said.

“Cocaine use is attributed with more violent crimes,” she said, and while the state is not necessarily seeing a spike in violence due directly to cocaine use, she added, it is something to keep in mind.

***

LaPrade depends on his social supports to remain in recovery and not relapse into drug use – particularly other people enrolled in McShin’s programs.

“McShin saved my life, hands down, without a doubt,” he said. “Everybody here has been to the depths of hell and back.”

His present circumstances are a far cry from where he was just a little over a year ago, when he was still in the grips of his addiction.

“I never, ever thought I could be happy again,” he said.