Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is a plant indigenous to Thailand and Southeast Asia. Kratom leaves produce complex stimulant and opioid-like analgesic effects. In Asia, kratom has been used to stave off fatigue and to manage pain, diarrhea, cough, and opioid withdrawal. Recently, kratom has become widely available in the United States and Europe by means of smoke shops and the Internet. Analyses of the medical literature and select Internet sites indicate that individuals in the United States are increasingly using kratom for the self-management of pain and opioid withdrawal. Kratom contains pharmacologically active constituents, most notably mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine. Kratom is illegal in many countries. Although it is still legal in the United States, the US Drug Enforcement Administration has placed kratom on its “Drugs and Chemicals of Concern” list. Physicians should be aware of the availability, user habits, and health effects of kratom. Further research on the therapeutic uses, toxic effects, and abuse potential of kratom and its constituent compounds are needed.

Throughout history, humans have used plant-derived materials (often referred to as “herbal” or “botanical” remedies) to treat diseases, cope with the stresses of life, and achieve altered states of awareness. Even with the development of modern pharmaceuticals and medical practices, many people still use herbal remedies either as alternatives to or in conjunction with mainstream medical care. Several years ago, Barnes et al

1 found that more than 30% of US patients had or were using some form of herbal-based remedy. They also noted that the agents were being used primarily for “musculoskeletal or other conditions involving chronic pain.”

1

Even though the efficacies of most of these herbal remedies have yet to be proven in controlled clinical trials, it is clear that such products are being used extensively. Whether they are consumed alone or in combination with prescribed medications, herbal remedies have the potential to cause toxic effects, interact with prescription drugs, and complicate the diagnosis and treatment of disease.

2 At the same time, however, herbal remedies may have substantial therapeutic effects. Some evidence

2 suggests that certain herbal products may, in fact, have therapeutic actions that are equivalent to those of modern pharmaceuticals. Moreover, research on the effects of herbal supplements and their active constituents may provide insight that could lead to the development of new and more effective therapeutic agents.

Given the extensive use of herbal remedies, it is important that physicians and other health care professionals have some knowledge of their attendant issues. This topic is especially relevant to osteopathic physicians because the tenets of osteopathic medicine focus on a unified approach to patient care, musculoskeletal health, and self-healing.

3 Osteopathic physicians should be familiar with common herbal remedies that their patients may be using. One herbal remedy that has been receiving increased public attention in recent years is kratom.

4 In the present article, we discuss current patterns of usage, basic pharmacology, legal standing, and medicinal potential of kratom.

The term

kratom refers to a group of tree-like plants belonging to the Mitragyna genus of the Rubiaceae family.

4–

9 Other members of the Rubiaceae family include the coffee and gardenia plants. From a medical perspective, the most important species of kratom is

Mitragyna speciosa, which is indigenous to Thailand and surrounding countries in Southeast Asia.

7 Images of a kratom plant and a kratom leaf are shown in

Figure 1.

Kratom has been widely used in Southeast Asia for hundreds of years.

5,

6 In Thailand, kratom use typically involves ingestion of the plant’s raw leaves or consumption of teas that are brewed or steeped from the leaves.

4,

6,

9 Kratom leaves are used for their complex, dose-dependent pharmacologic effects.

4,

6,

9–

12 Low to moderate doses (1-5 g) of the leaves reportedly produce mild stimulant effects that enable workers to stave off fatigue.

6,

9–

11,

13 Moderate to high doses (5-15 g) are reported to have opioid-like effects.

6,

9–

11,

13 At these doses, kratom has been used for the management of pain, diarrhea, and opioid withdrawal symptoms, as well as for its properties as a euphoriant.

5,

6,

9–

11,

14 Very high doses (>15 g) of kratom tend to be quite sedating and can induce stupor, mimicking opioid effects.

4,

5,

9

Despite its long history and widespread use in Southeast Asia, kratom has only recently begun to receive attention and be used as an herbal remedy in the West. The emergence of kratom as a product or drug of interest in the United States is evident from the results of our literature search. Our search of the US National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database in February 2012, using the keyword “kratom,” yielded a total of 35 published articles and reviews. Of those, 30 (86%) were published in or after 2004, 4 (11%) were published between 1988 and 1997, and 1 (3%) was published in 1975. Another PubMed search, using the keywords “Mitragyna speciosa,” yielded a total of 65 published articles. Of those, 49 (75%) were published within the past 10 years.

In addition to these general trends in the number of publications on kratom, we found that an increasing number of reports of adverse effects resulting from the use of kratom have been published.15-19 Recent news reports have highlighted the increasing level of kratom use, particularly among college-aged populations.

20,

21 Moreover, published studies indicate that vast numbers of online vendors and general information Web sites for kratom have appeared in the past few years, suggesting that there is a substantial demand for kratom products.

22,

23

In February 2012, we also conducted an Internet search using the Google search engine. A search for the keyword “kratom” found more than 2 million results. Of the first 100 Web sites listed in the search results, 78 were primarily focused on the sale of kratom, while 22 Web sites primarily focused on disseminating information about kratom through the use of discussion boards. We want to strongly emphasize that the scientific validity of the claims and anecdotes reported on these Web sites has not been substantiated. Moreover, for the purpose of the present review, we did not believe it was appropriate to cite all sources of anecdotal information. However, we did find 3 Web sites to be particularly informative:

Erowid.org24;

Sagewisdom.org25; and

WebMD.com26. These Web sites contain a variety of information including the drug’s uses and effects, discussions of individuals’ personal experiences, and adverse reactions when using kratom. Some of the Web sites

24,

25 even describe the biology of

Mitragyna speciosa, including optimal methods and conditions for growing. In addition, an analysis by León et al

7 suggests cultivation exists here in the United States. It is also important to note that much of the content of these Web sites clearly indicates that kratom is being used for medicinal purposes. Although some sites

24–

26 portray users of kratom as recreational drug users, many posts on kratom blogs are from patients dealing with pain management issues.

24–

26 In some cases,

24–

26 individuals report finding relief of various types of pain with kratom use. In addition, recent publications have highlighted the use of kratom products for the self-management of opioid withdrawal symptoms.

20,

27Although the anecdotal claims reported on the aforementioned Web sites and publications have not been substantiated, their existence indicates that kratom is being used in these contexts.

Although the findings of our literature and Internet searches strongly suggest a marked increase in kratom use in the United States and Europe, kratom still appears to be somewhat of an “underground phenomenon.” During our searches of the literature and the internet, we found no evidence that kratom is currently marketed by any of the large nutritional supplement chain stores in the United States. However, a wide variety of kratom products—including raw leaves, capsules, tablets, and concentrated extracts—are readily available from Internet-based suppliers.

20,

21 In addition, these products are often sold in specialty stores commonly known as “head shops” or “smoke shops.” In February 2012, our own informal in-person and telephone survey of 5 smoke shops in the metropolitan Chicago area revealed that purported kratom products were available in all of them.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show images of several kratom products (ie, chopped leaves, capsules, and pressed tablets) that were legally purchased at a smoke shop in suburban Chicago.

From a legal standpoint, kratom is regulated as an herbal product under US law and US Food and Drug Administration and US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) policies. As of this writing,

Mitragyna speciosa (kratom) is not prohibited by the Controlled Substances Act

28 and is considered a legal substance in the United States. However, the DEA’s December 2010 version of the Drugs and Chemicals of Concern list states that “there is no legitimate medical use for kratom in the U.S.”

29 Therefore, it cannot legally be advertised as a remedy for any medical condition.

As the use of kratom in the West has grown during the past 15 years,

4,

20,

23,

30there have been increased efforts to identify and characterize the active pharmacologic agents that mediate the effects of kratom in the body. Thus far, more than 20 active compounds have been isolated from kratom, and considerable evidence shows that these compounds do, in fact, have major pharmacologic effects.

30,

31 Various aspects of the medicinal chemistry and pharmacognosy of kratom have recently been reviewed by Adkins et al.

30Accordingly, only a few key points regarding these topics will be considered in the present article. The

Table shows the chemical structures and summarizes the major pharmacologic actions of some of the kratom-derived compounds that have been studied most extensively. The most extensively-characterized of kratom’s active pharmacologic agents have been the mitragynine analogs.

30These agents contain an indole ring and are, in some respects, structurally similar to yohimbine.

30 These agents have been shown to produce a wide variety of pharmacologic effects, both in vivo and in vitro.

30 In the following sections, we will consider the importance of these compounds as they relate to the primary pharmacologic effects of kratom, particularly analgesia and the ability to suppress symptoms of opioid withdrawal.

In Southeast Asia, kratom has long been used for the management of pain and opium withdrawal.

6,

9–

11,

14 In the West, kratom is increasingly being used by individuals for the self-management of pain or withdrawal from opioid drugs such as heroin and prescription pain relievers.

20,

27 It is these aspects of kratom pharmacology that have received the most scientific attention. Although to our knowledge, no well-controlled clinical studies on the effects of kratom on humans have been published, there is evidence

30–

38 that kratom, kratom extracts, and molecules isolated from kratom can alleviate various forms of pain in animal models. Studies have used a variety of methods including hot plate,

35,

37,

39 tail flick,

32,

39 writhing,

37,

38 and pressure/inflammation

35,

38 tests in mice

32,

35,

38,

39 and rats,

35,

37 as well as more elaborate tests in dogs and cats.

35In addition, a variety of chemical compounds have been isolated from kratom and shown to exhibit opioid-like activity on smooth muscle systems

31,

33,

34 and in ligand-binding studies.

39,

40 Most notably, many of the central nervous system and peripheral effects of these kratom-derived substances are sensitive to inhibition by opioid antagonists.

31–

34,

39–

41

Most of the opioid-like activity of kratom has been attributed to the presence of the indole alkaloids, mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine. Both compounds have been shown to have analgesic and antinociceptive effects in animals, although 7-hydroxymitragynime is more potent.

30,

32,

40 These agents also produce opioid-like effects on organs such as the intestines and male internal genitalia.

33,

34 Moreover, when they are given to animals for 5 days or longer, both compounds produce a state of physical dependence, with withdrawal symptoms that resemble those of opioid withdrawal.

31,

32,

41 In addition, ligand-binding studies and those using opioid antagonists indicate that these effects are largely mediated by means of actions on μ- and δ-type opioid receptors.

30,

31,

33 Along with these various central nervous system effects, kratom also appears to have anti-inflammatory activity.

38 Utar et al

42 recently found that mitragynine can inhibit lipopolysaccharide-stimulated cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production. In addition to direct mediation by means of opioid receptors, the antinociceptive effects of mitragynine appear to involve the activation of descending noradrenergic and serotonergic pathways in the spinal cord.

43 Additionally, animal studies have shown that mitragynine may stimulate postsynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors and possibly even block 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors.

33 Although kratom contains lower levels of 7-hydroxymitragynine than mitragynine, it has been suggested that 7-hydroxymitragynine is more potent and has better oral bioavailability and blood brain-barrier penetration than mitragynine,

30,

40 making it the predominant mediator of analgesic effects of kratom in the body.

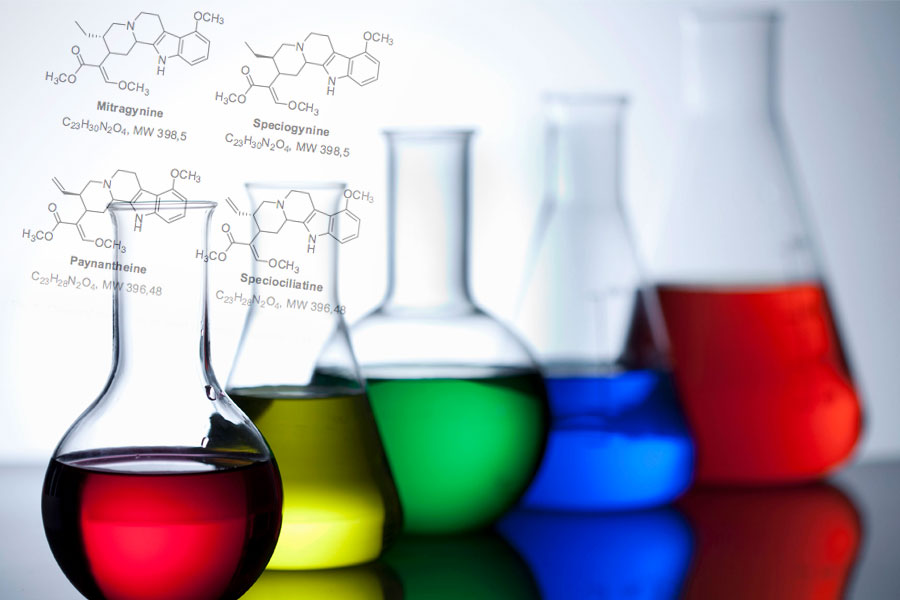

Other compounds that have been isolated from kratom and implicated in some of its effects include speciociliatine, speciogynine, and paynatheine.

30,

40 These compounds have been shown to modulate intestinal smooth muscle function and behavioral response in animals.

33,

34,

40,

44 However, these effects were not inhibited by the opioid receptor antagonist naloxone, suggesting that they involve opioid-independent mechanisms.

40,

44 It remains to be determined how these compounds may contribute to the overall actions of kratom in vivo.

In spite of the fact that kratom has been widely touted and used as a “legal opioid,”

23,

31 few scientific studies have addressed the psychoactive properties of kratom.

6,

9,

11,

12 Most of the available information is based on anecdotal reports and patient experiences. The general subjective effects of kratom have been summarized in various reviews.

6,

9,

12,

30 In addition, many individuals have posted descriptions of their personal kratom experiences on Web sites such as Erowid, Sagewisdom, and WebMD.

24–

26 As noted previously, kratom produces an unusual combination of stimulant- and opioid-like effects. These effects are highly dependent on the dose of kratom and can vary markedly from one individual to another. Low to moderate doses (1-5 g of raw leaves) usually produce a mild stimulant effect that most individuals perceive as pleasant but not as intense as those of amphetamine-like drugs.

24,

25 Some individuals, however, report that these low-dose effects are mainly characterized by an unpleasant sense of anxiety and internal agitation.

24–

26 It is noteworthy that those who have used kratom products for pain management tend to view the stimulant effects of kratom as being more desirable than the sedative effects of traditional opioids.

24–

26

Opioid-like effects, such as analgesia, constipation, euphoria, and sedation are typically associated with the use of moderate-high doses of kratom (5-15 g). As with the lower-dose effects, the higher-dose effects may be either euphoric or dysphoric, depending on the individual. Of note, the euphoric effects of kratom generally tend to be less intense than those of opium and opioid drugs.

6,

10,

11,

25Nevertheless, kratom is still sought by drug users.

During the past 3 years, there have been an increasing number of case reports

15,

17,

29 describing unusual adverse reactions in patients who had been using kratom or kratom-based products. The acute adverse effects of kratom experienced by many users appear to be a direct result of kratom’s stimulant and opioid activities.

6,

9,

11,

30,

31 Stimulant effects may manifest themselves in some individuals as anxiety, irritability, and increased aggression. Opioid-like effects include sedation, nausea, constipation, and itching. Again, these effects appear to be dose dependent and to vary markedly from one individual to another. Chronic, high-dose usage has been associated with several unusual effects. Hyperpigmentation of the cheeks, tremor, anorexia, weight loss, and psychosis have been observed in individuals with long-term addiction.

9 Reports of serious toxic effects are rare and have usually involved the use of relatively high doses of kratom (>15 g).

9,

17,

45,

46 Of particular concern, there have been several recent reports of seizures occurring in individuals who have used high doses of kratom, either alone or in combination with other drugs, such as modafinil.

17,

22,

45 Kapp et al

15 recently described a case of intrahepatic cholestasis in a chronic user of kratom.

It is important to note that in each of these case reports, the patients may have had confounding health conditions, may have been using other drugs along with kratom, or both. One of the major problems in evaluating the potential uses and safety of an herbal agent such as kratom is the lack of understanding of how substances in kratom may interact with prescription medications, drugs of abuse, or even other herbal supplements. This issue is compounded by the relative lack of regulations and standardization related to the production and sale of kratom. These potential hazards were highlighted in several case reports of deaths resulting from the use of a kratom-based product known as “Krypton”.

16,

47 This agent, which was touted as a very potent form of kratom, had been marketed in Sweden. During the past 5 years, there have been reports of 9 deaths related to the use of Krypton.

16 In a case series by Kronstad et al,

16subsequent forensic studies revealed that Krypton contained high amounts of the exogenous pharmaceutical agent

O-desmethyltramadol, which has opioid and neuromodulator activity. Evidently, the exogenous

O-desmethyltramadol had been added to the plant material. Even though mitragynine was also detected in the products, it was not determined how the 2 substances may have interacted to cause death. Another recent report

48 described a fatal reaction that appeared to be associated with the use of a combination of propylhexedrine—an α agonist and an amphetamine-like stimulant—and mitragynine. This latter case highlights the fact that extracts and tinctures containing purified mitragynine, 7-hydroxymitragynine, and 7-acetoxymitragynine have become available for purchase by means of the Internet. These sources can easily be found by conducting an Internet search using the term “mitragynine purchase.” The possibility that these highly concentrated mitragynine alkaloid extracts could be used in conjunction with other psychoactive drugs (eg, alcohol, sedatives, opioids, stimulants, cannabinoids) raises the potential for serious drug interactions.

A large number of Internet posts refer to the use of kratom as a euphoriant or “legal opioid.”

23–

26 A major question that remains unanswered is, “How addictive is kratom?” Although many anecdotal reports suggest that it may be less addictive than classical opioids, there are also numerous reports that, in some individuals, it may be highly addictive. For example, in Southeast Asia, it has long been recognized that individuals will seek out and abuse kratom for its euphoric and mind-altering effects and that chronic users can become tolerant of, physically dependent on, and addicted to kratom.

9,

10 Kratom addiction is considered such a problem that many Southeast Asian countries have outlawed the use of kratom.

9,

10

As kratom use has expanded to Europe and the United States, there have been increasing reports of individuals becoming physically dependent on or addicted to kratom.

22,

30,

31,

45,

46 Most published studies are case reports

22,

31,

45,

46 of heavy, compulsive users of kratom. In each case, the individual exhibited substantial tolerance to the effects of kratom and showed overt symptoms of withdrawal when kratom use was stopped. The symptoms of withdrawal were similar to those from traditional opioids and included irritability, dysphoria, nausea, hypertension, insomnia, yawning, rhinorrhea, myalgia, diarrhea, and arthralgias. In a recent report, McWhirter and Morris

45 described the use of an opioid agonist (dihydrocodeine) and an α-adrenergic antagonist (lofexidine) to successfully manage symptoms of withdrawal in an individual who was addicted to kratom.

Kratom and kratom-derived compounds such as mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine are not detected in most routine drug testing or screening procedures.

49 Although various tests for kratom-derived compounds have been developed,

49 they are not yet widely available for general use. Moreover, there are still some controversies regarding the designation of drug-level cutoff points for defining the tests.

49 The analytical and forensic aspects of kratom toxicology have been summarized in a review by Philipp et al.

49

Evidence suggests that kratom is being used extensively for both medical and nonmedical purposes. Recent studies have shown that kratom contains a variety of active compounds that produce major pharmacologic effects at opioid and other receptors. Kratom and kratom-derived drugs may potentially be used for the management of pain, opioid withdrawal symptoms, and other clinical problems. At the same time, serious questions remain regarding the potential toxic effects and the abuse and addiction potential of kratom. This issue is further confounded by the lack of quality control and standardization in the production and sale of kratom products. The possibilities of kratom products being adulterated or interacting with other drugs are also serious concerns. Until these issues are resolved, it would not be appropriate for physicians to recommend kratom for the treatment of patients. Nevertheless, physicians need to be aware that patients may use kratom or kratom-based products on their own. Further studies to clarify the efficacy, safety, and addiction potential of kratom are needed.

The authors thank Victoria Sears and Laura Phelps, MA, in the Department of Pharmacology at Midwestern University for their help in preparing the manuscript. The authors also thank Susan Hershberg at Midwestern University for her assistance in capturing the photographic images of the kratom products.