Advocates believe the powder helps people kick opioids without risk of addiction. When the DEA tried to criminalize it, they fought back.

For days, Susan Ash woke around noon, ate a bowl of cereal, and went back to bed. That was all the living her pain would allow. Her neck hurt, her hips hurt, her knees and feet and toes hurt. “I felt like I’d been electrocuted,” she recalls. Her doctor in Portland, Ore., diagnosed her with fibromyalgia, possibly caused by past car and bicycle accidents. She tried physical therapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic care, to no avail. In 2008, at 38 years old, she sublet her apartment and moved to Norfolk, Va., where she’d grown up. “While all my friends got married and had kids,” says Ash, a delicate blonde, “I was at home living with my parents. And I was sick.”

To counteract her aches, she took three or four 30-milligram extended-release morphine pills a day, plus immediate-release ones as needed. Eventually her new physician decided she didn’t have fibromyalgia, but Lyme disease. Since it was diagnosed so late, the doctor told her, it would likely afflict her for the rest of her life. By then addicted to morphine, Ash added Dilaudid, a semi-synthetic opioid, to her regimen, then shifted to oxymorphone, another addictive opioid. Then, she says, “I lost all control.” She started snorting crushed oxymorphone pills off a makeup mirror to get a faster, stronger high. She’d use a month’s ration in three weeks, then endure a week of withdrawal.

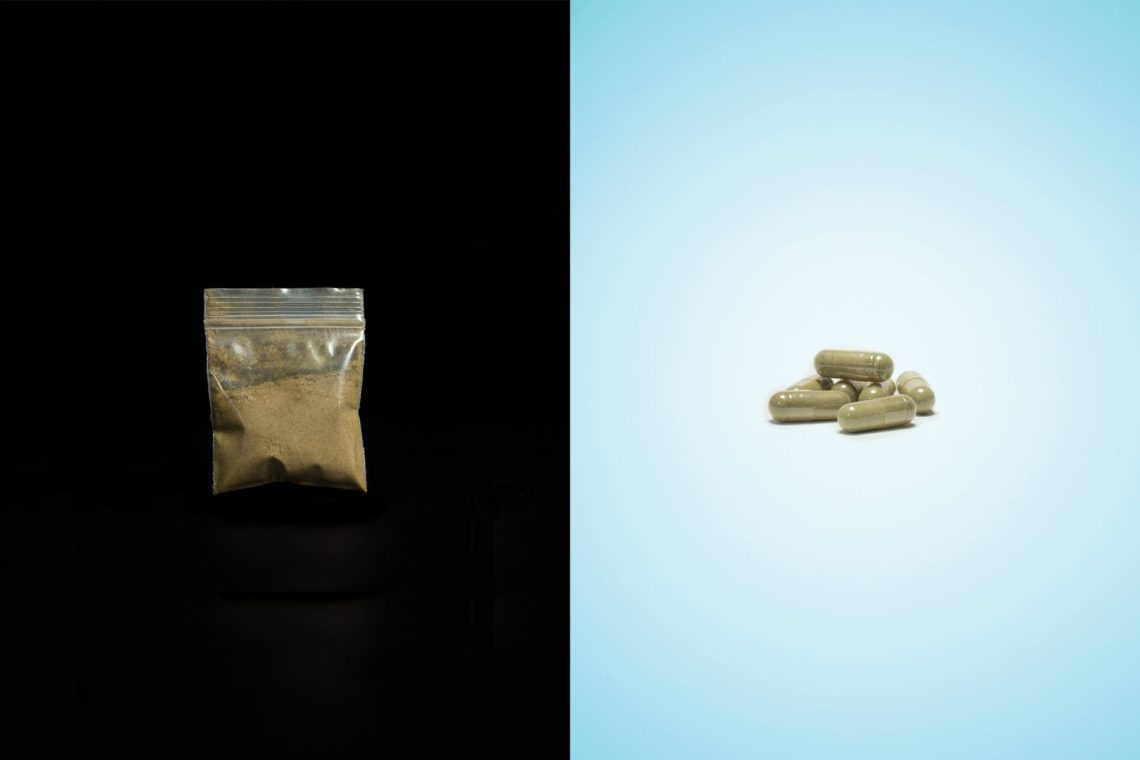

Once, after her prescription ran out, she wrote on Facebook that she’d lost it, hoping someone would get her some pills. A woman she didn’t know suggested she try kratom, a green powder derived from the crushed leaves of an eponymous tree indigenous to Southeast Asia. Ash scoffed. “I didn’t care about a plant,” she says. “I was like, ‘Just send me your drugs.’ ” Eventually, though, she ordered some kratom capsules online.

They came in an unmarked zip-lock bag. Ash took six, and within 45 minutes, she says, her pain and withdrawal symptoms had become manageable. It didn’t deliver much of a high, but soon she was regularly using the stuff after her oxymorphone ran out. Finally, she decided to switch to kratom altogether. Several times a day, she brewed the powder into tea or ate it dry despite its dirtlike taste, washing it down with water. Her pain and opioid cravings subsided, her energy returned, and her mind cleared. “I was like a different person,” she says.

Ash became such a fervent believer that last year she founded the American Kratom Association to promote the product and represent its users nationwide. At the time, kratom or at least one of its active ingredients was banned in Indiana, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Several more U.S. states were considering restrictions, concerned that the substance was yet another addictive, gray-market high. Kratom was also prohibited or treated as a controlled drug in at least 10 countries, including Australia, Malaysia, Poland, and Thailand.

Backed by donations, Ash spent her first year as head of the AKA lobbying legislators in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, New York, and North Carolina, arguing that kratom was a safe alternative to legal and illegal opioids, which had caused more than 28,000 overdose deaths in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But as she was hopscotching state capitals, officials at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency were preparing an unwelcome surprise. One morning this August, as Ash was packing up to move back to Portland with the idea of reclaiming her independence, someone sent her an article saying that the DEA was planning to place kratom on its list of Schedule I narcotics—the agency’s equivalent of the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. The DEA and FDA had determined that kratom posed an “imminent hazard to public safety” on the order of heroin and LSD. Once on Schedule I, kratom would be regulated more strictly than opioids such as oxycodone, which is classified as a Schedule II drug. These drugs also have a high potential for abuse, but they have an accepted medical use for treating pain.

The finding gave the DEA the authority to declare kratom illegal in as little as 30 days. Using, selling, distributing, and marketing it would be subject to felony prosecution, prison, and fines. Just like that, Ash and her fellow devotees might face the choice of becoming criminals or going back to the opiates they maintained had poisoned their lives. She postponed her return to Oregon, set up her laptop and iPad in her parents’ dining room, and went to work, convinced the DEA was targeting a potential antidote to the overdose plague—a substance that had all the benefits of powerful opioids, without the dangers.

The glossy green leaves of the kratom tree, part of the coffee family, have been consumed for centuries in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and neighboring countries. Farmworkers believed that chewing the leaves gave them energy during long, sweltering days, and that larger amounts helped treat coughing, diarrhea, chronic pain, and opium addiction. The tree’s name is pronounced KRAY-tom, KRAH-tom, or krah-TUM, depending on the speaker, while its consumable form is variously referred to as kakuam, biak-biak, mambog, ithang, and ketum, among other names. A premium variety, maeng da, is widely translated as “pimp grade.”

Kratom gained popularity in the U.S. over the past decade or so, as its availability spread online and in head shops. Two or 3 grams of powdered extract steeped in hot water or whipped into a smoothie offers a mild, coffee-like buzz; doses double or triple that size can induce a euphoria that eases pain without some of the hazardous side effects of prescription analgesics. Preliminary survey data gathered recently by Oliver Grundmann, a pharmaceutical sciences professor at the University of Florida, found that American users are mostly male (57 percent), white (89 percent), educated (82 percent with some college), and employed (72 percent). More than 54 percent are 31 to 50 years old, and 47 percent earn at least $75,000 a year.

In the U.S., the kratom business consists mostly of retailers who buy raw leaf product from overseas farmers or a distributor. There are also wholesalers who package and encapsulate the stuff, though some retailers contract this out themselves. A recent survey by the Botanical Education Alliance, a business lobby group, counted about 10,000 vendors with annual revenue slightly over $1 billion.

At the CBD Kratom shop in Chicago, Andrew Goth, a 28-year-old salesman with earlobe expanders and a Harry Potter–style lightning-bolt tattoo beneath his Adam’s apple, describes having shoppers twice his age who rely on kratom to relieve joint and back pain. “Customers who take two or three OxyContins or Percocets can’t be productive throughout the day,” he says. “On kratom they can.” Goth uses it to aid his recovery from addiction to cocaine and alcohol.

Along a brick wall, facing a portrait of Bob Marley, shelves of glass jars display strains with names like Green Cambodian, White Borneo, and Super Indo. Foil packs of 10 0.55-gram capsules sell for $7.95, raw powder is $1 a gram, and 2-ounce Bali Liquid Gold Shots go for $9.95. Kratom can also be found at convenience stores and kava bars (kava, a derivative of a South Pacific plant, is a trendy alcohol substitute), but the bulk is sold via Craigslist and online retailers such as Kratom-K and Kratora Quality Ethnobotanicals.

Some of these sites include legalistic and occasionally disingenuous disclaimers. “These products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease,” Kratom-K’s website says. “These products are not intended for human or animal consumption.” The site also advises visitors, “Don’t go stocking your sideboard full of Green Thai kratom if you’re questing after relaxation. However, do stock it when in hot pursuit of stimulation power.”

The underpinnings of kratom’s stimulation power are broadly known in the scientific community, though virtually all research into the drug has been restricted to animals. Kratom works a lot like morphine. It contains two key alkaloids—mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine—that bind with proteins called Mu receptors, a class of opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord. Once activated, a Mu receptor acts like a dimmer switch, dulling pain signals from around the body. When someone takes morphine and other opioids, these receptors also trigger neural pathways that can prompt the brain to turn off breathing—the primary cause of overdose death. For reasons that aren’t clear, kratom’s alkaloids avoid those perilous trails.

“Ain’t that cool?” says Edward Boyer, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. “There’s a lot of super sexy research you could do with this.” Some investigation is taking place abroad—in 2014, scientists in Japan reported creating a kratom derivative 240 times as effective at pain relief as morphine. In the U.S., Boyer and researchers at the University of Mississippi are seeking a patent on methods of treating addiction withdrawal using kratom extract. If the drug were on Schedule I, they would be required to get a DEA license and ensure, among other costly steps, that their supply was safe from theft.

Scientists disagree on whether kratom is addictive, but it has been observed in animals that its alkaloids also attach to the Kappa opioid receptor, which creates an aversion to opioid cravings. Absent formal research on humans, feel-good stories like Ash’s vie with case studies such as one published by the Wisconsin Medical Society, which describes a 37-year-old teacher who admitted herself to an addiction clinic because she couldn’t cold-turkey kratom. Boyer recalls one patient who mixed leaf powder into a solution and injected it. “If that’s not problematic drug use,” he says, “I don’t know what is.”

The U.S. government didn’t pay much attention to kratom until July 2013. That month, three advocacy groups sent a one-page letter to Daniel Fabricant, who was then the director of the FDA division that oversees the dietary supplement industry, which has annual revenues of $30 billion or more. The letter was co-signed by the heads of the United Natural Products Alliance, the Council for Responsible Nutrition, and the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, organizations representing dietary supplement producers and marketers such as Herbalife, Bayer, and Pfizer—but not, notably, any kratom vendors. “Given the widespread availability of kratom,” the letter said, “the dietary supplement industry is concerned about the potential dangers to consumers who may believe that they are consuming a safe, regulated product when they are not.” The organizations asked the FDA to “deter further marketing of kratom under the mistaken belief that it is a legitimate product.”

The letter may have been motivated partly by kratom’s growing sales. But supplement companies are also sensitive to the perception that their business is lightly regulated and rife with empty health promises and half-baked science. As it stood, the FDA classified kratom both as a supplement, like protein powder, and as an unapproved drug. The industry groups believed the agency wasn’t giving kratom enough scrutiny. “We became aware it was being sold as a dietary supplement, and that raised red flags,” says Steve Mister, president and chief executive officer of the Council for Responsible Nutrition. “If it’s going to be in the marketplace, the FDA needs to enforce the law to protect the integrity of the law.”

The 1994 statute governing dietary supplements requires marketers to prove that new products or ingredients will be reasonably safe, upon which the FDA conducts a 75-day vetting that’s far less rigorous than the review pharmaceutical makers face. The agency doesn’t approve supplements per se, but if it identifies problems, it can take steps to get products off the market. Some supplement makers skip the process, hoping the FDA won’t notice, and as of July 2013, no kratom marketers had informed the agency about their products, even though tons of the leaf were coming into U.S. ports. According to Fabricant, some importers would mislabel kratom as incense, potpourri, or cosmetics, or mark packages “not for human consumption,” even though their websites said otherwise.

The supplement businesses found a receptive audience in Fabricant, who’d joined the FDA in 2011 after working as a vice president for the Natural Products Association, another supplement lobbying group. He’d already been highlighting safety concerns about kratom at trade show presentations before the letter arrived. Seven months after he received it, the FDA issued Import Alert 54-15, which raised “concerns regarding the toxicity of kratom in multiple organ systems.” The alert directed field agents to detain packages arriving from Canada, Indonesia, and Malaysia that they suspected of containing the product. It didn’t cite evidence to support the toxicity claim.

At the time, the DEA seemed less worried than the FDA. The DEA had listed kratom as a “drug of concern” for several years, but spokeswoman Barbara Carreno told the trade publication Natural Products Insider in March 2014 that kratom had “not been a big enough problem in the U.S. to control.” That posture changed several months later. On the afternoon of July 16, 2014, according to the Palm Beach Post, a 20-year-old Ian Mautner drove to an overpass in Boynton Beach, Fla., left his Isuzu Trooper, removed his sandals, and threw himself to his death on Interstate 95 below. Police found packets of kratom in his vehicle. Lab tests showed mitragynine, as well as prescription antidepressants, in his blood. He hadn’t left a suicide note.

Ian’s mother, Linda Mautner, blamed her son’s death on kratom addiction, telling the FDA that her son had ingested the leaf frequently, causing him to suffer from weight loss, vomiting, constipation, and hallucinations, among other problems. He had dropped out of college and entered rehab, but relapsed the month before he died.

Five weeks later, the DEA asked the FDA for a recommendation on whether to name kratom a controlled substance. In most cases, federal law requires an eight-factor FDA analysis before the DEA can list something on one of its five Schedules. Cough and anti-diarrhea treatments reside at the low end of the spectrum, Schedule V, whereas Schedule I drugs have “no currently accepted medical use and high potential for abuse.”

Officials for the FDA and DEA declined to be interviewed for this story, but DEA spokeswoman Carreno says her agency sought the FDA study in part because some states and other countries had begun regulating kratom. “The plant was particularly concerning amidst an opioid crisis,” she adds. The import alert had helped to identify a rise in kratom shipments, and to expose that many were entering the country clandestinely—something that figures in the DEA’s calculus of whether a substance should be legally controlled. The FDA was also getting complaints that kratom had made some consumers ill, and that they were having withdrawal symptoms when they tried to quit.

In September 2014, the U.S. Marshals Service executed the FDA’s first formal seizure of kratom, confiscating more than 25,000 pounds of raw leaf valued at $5 million from a Southern California importer. “We have identified kratom as a botanical substance that poses a risk to public health and has the potential for abuse,” said Melinda Plaisier, the FDA’s associate commissioner for regulatory affairs. “This action was taken to safeguard the public from this dangerous product.”

By then, Ash was living at her parents’ red-brick cape Cod house along the Lafayette River in Norfolk, collecting $1,100 monthly disability payments, using kratom every day, and mentoring painkiller addicts on how to make the transition from opioids. “These were broken people, and this is the scariest time in their whole lives when they finally make a decision to get off of opioids,” she says. “I was literally helping little old ladies who didn’t want to take oxycodone anymore.”

Ash was also keeping tabs on the state legislatures that were considering kratom bans. The Botanical Education Alliance (then called Botanical Legal Defense) had begun lobbying against restrictions on behalf of kratom businesses, and Ash decided to start an association that would represent consumers. A vendor staked her the $373 in fees that she needed to register the group, which she called the American Kratom Association, and she launched the organization’s website in February 2015.

A former volunteer park ranger and self-described hippie chick who has seen the Grateful Dead 37 times, Ash had worked for forest preservation nonprofits in Utah and Oregon. Advocacy came naturally to her. In the next year and a half, she told her story to lawmakers in five states. She says many officials knew little about kratom and tended to lump it in with addictive synthetics such as so-called bath salts. She once testified at a legislative hearing in Florida that also included remarks from Linda Mautner; Ash says she empathized with Mautner but believes there were reasons other than kratom for her son’s death, while Mautner says kratom proponents “were very angry with me, because I exposed it.” Despite Ash’s lobbying efforts, Arkansas and Alabama passed bans, the fifth and sixth states to do so.

In Washington, as lawmakers pressed regulators for action on the opioid epidemic, the FDA and DEA were building a case against kratom. They compiled research showing that calls about kratom-related illnesses to poison centers had risen tenfold since 2010. Reports from forensic labs about trafficking and abuse were up, too. Shipments amounting to 12 million kratom doses had been confiscated or detained at the border. And the DEA counted at least 30 worldwide deaths since 2009 as kratom-related. By early 2016, both agencies viewed kratom use not as a vehicle for recovery from opioid abuse, but as a precursor to relapse.

The FDA analysis sought by the DEA still wasn’t done in May, when DEA Acting Administrator Chuck Rosenberg decided—without the FDA objecting—to criminalize kratom immediately. Scheduling a narcotic typically takes years, but in 1984 Congress let the DEA proceed faster with drugs the agency says pose an “imminent hazard” to the public. In the past two years, it has used the procedure to put the synthetic cannabinoid MAB-CHMINACA (multiple overdoses, four deaths) and the opioids acetyl fentanyl (39 deaths) and U-47700 (15 deaths) on Schedule I.

The DEA issued its formal notice about kratom on Aug. 30, calling it “an increasingly popular drug of abuse readily available on the recreational drug market.” By law, the DEA’s final ruling wasn’t subject to court review. Nor did it require public comment.

“I had a lot of panicked people on my hands,” Ash says. From the Queen Anne table in her parents’ dining room, with the family mutt, Dash, snoozing at her feet, she started working the phone, e-mail, and social media. “We are now facing our darkest hour,” she wrote on AKA’s Facebook page on Sept. 3. The challenge was close to hopeless. The DEA had never changed its mind about scheduling a drug on an emergency basis. And once a substance is on Schedule I, it’s almost impossible to dislodge, as marijuana supporters know; the agency this summer rejected the recent bid to de-schedule weed, even as legal U.S. sales of medical and recreational marijuana are projected to reach $7 billion this year.

Within a week, the Botanical Education Alliance and Ash’s association hired a lobbyist, a public-relations company, and the Washington law firms Venable and Hogan Lovells, where Rosenberg had once been a partner. Ash also went on what she calls “a fundraising rampage.” Donations and $20 membership fees poured in, including a $100,000 gift from a retailer. In a few weeks, the association’s bank account swelled from $30,000 to $300,000. By December, it would reach $430,000.

More than 130,000 supporters signed a whitehouse.gov petition seeking to stop the DEA. At a rally near the White House on Sept. 13, demonstrators in “Kratom saved my mom” T-shirts flogged the petition and served kratom tea. Disabled military veterans and others posted “I Am Kratom” video testimonials on social media.

On Capitol Hill, Representative Mark Pocan, a Wisconsin Democrat, received an e-mail from a friend in Colorado who relies on kratom to neutralize various ailments. After reading the DEA decision and deciding that the agency had used what he calls “a nonprocess with a lot of pretty shaky science,” he invited Ash to D.C. for a chat. Eventually he and Matt Salmon, a Republican representative from Arizona, recruited 49 House members to co-sign a letter urging Rosenberg to delay a final decision and allow for public comment. In a separate letter, six university researchers argued that a ban would jeopardize their promising work on kratom derivatives.

The public backlash surprised the DEA, which rarely gets such outcry over decisions not involving marijuana. As Pocan says, “This is hardly the tie-dye psychedelic crowd. These are people in their 30s, 40s, 50s with serious diseases and conditions who had to go to pain meds and got addicted.”

The kratom advocates’ law firms also sent letters to the DEA. Hogan Lovells’s 35-page missive included an extra 51 pages of testimonials from kratom users. “This is LIFE and DEATH for hundreds of thousands of Americans,” wrote an unnamed 39-year-old woman who said she was suffering from muscular dystrophy and back pain. “This plant has brought nothing but good into my life and if it’s ripped away, I fear for my very life.”

Point by point, Hogan Lovells’s letter attacked the government brief that sought to make kratom the legal equivalent of LSD. The firm argued that no reports in scientific journals had ever attributed a death solely to kratom use, and that all of the fatalities the DEA had cited also involved alcohol, narcotics, or underlying medical conditions—something the DEA’s own accounting acknowledged in all but one instance. Nine fatalities in Sweden that the agency had listed, for example, could be traced to a product, Krypton, that was laced with the synthetic opioid tramadol, which in large doses can inhibit breathing. Other deaths had been complicated by heroin, fentanyl, and in one case a gunshot to the head.

More than 200 of the 660 kratom-related calls to poison centers had also involved alcohol, narcotics, or benzodiazepines, Hogan Lovells said. “Never before has DEA invoked its emergency scheduling authority to take action against a natural product with a long history of safe use in the community,” the letter read. It was signed by David Fox and Lynn Mehler, former lawyers in the FDA’s Office of Chief Counsel. According to Ash, the letter cost her organization $180,000.

It appears to have been worth it. September ended without DEA action. Then, on Oct. 12, the agency shocked the kratom community by withdrawing its emergency plan. Instead, it would allow six weeks of public comment before taking any action. Spokesman Russell Baer told Scientific American that the DEA still believed kratom was dangerous, but said “we don’t want the public to believe we are simply a group of government bureaucrats who don’t care about their safety and health.”

David Derian learned of the turnabout in a text message. “I couldn’t stop crying for about an hour,” he says. Derian, 43, started using kratom about six years ago, after enduring more than a decade of addiction to opioids prescribed for chronic back pain. In September, the company he founded, INI Botanicals, became the second kratom marketer to formally seek FDA acceptance of its products as dietary supplements. (Another company’s application was rejected by the FDA last year.)

In preparation for the submission, INI stopped selling its kratom offerings, which it sells under the brand Lucky Botanicals, and started commissioning scientific studies. “We wanted to become part of the solution and not add to the problem,” Derian says. He calls working with the FDA “refreshing and exciting,” adding, “they’ve been nothing but helpful.” If the DEA continues its tactical retreat, Derian plans to start selling a kratom product called Mitrasafe.

“I’d like to see this industry as regulated as the dietary supplement industry,” Ash says. “Nothing’s being sold in the U.S. that can compare to how unregulated this industry is. I know there are some bad people out there.” For now, the FDA is still working on its eight-factor analysis, and the DEA must pore over the more than 22,000 public comments it received. It’s not clear when the DEA will take its next step, but it could be to resume the emergency scheduling, launch a lengthier review, or leave kratom alone.

Earlier this year, Ash tore the meniscus in her right knee while walking in heels. Doctors prescribed oxycodone for the pain. She says she gave the pills to her mom, to dole out in strict accordance with the prescription. “They just didn’t do what I, as an addict, expected them to do,” she says. When the oxy was gone, she went back to kratom.

Now, Ash wonders what she’ll do if kratom is outlawed. “I don’t have very good choices,” she says. She finally moved back to Portland in October, and on stressful days, she feels a familiar craving. “If I could just take opiates,” she says, joking, “like in the good old days.”